Dispelling The Myths Of Sustainable Behavior

Last Friday I made it down to a local sustainability event, headed by Trondheim design group Eggs. While I was there to hear an inspiring story of learning, commitment and passion, during the event a few of the same, tired myths around sustainable behaviour cropped up.

The talk I was interested in was to be given by designer Sonya Swan, and detailed her efforts to get by on one tonne of CO2 equivalents for an entire year – well below the national average here in Norway.

I’ve been immersed for the last 20 months in helping local governments enable sustainable lifestyles for their citizens, and I was keen to come back to a more personal experience. Seeing the efforts of people who are sick of waiting for systemic change, and have decided instead to make sweeping changes to their own lifestyles is always an inspiration.

The story itself was inspiring. Despite working with these sorts of figures on a daily basis, I was surprised by how non-drastic many of the changes seemed, and how one person’s ongoing commitment to small, consistent changes really ended up adding up to a huge reduction in CO2e emissions. You had the big, critical changes, like foregoing plane rides, avoiding car use and going meat-free. But there was also research I hadn’t heard so much about, like sourcing seaweed as food and monitoring the sustainability of long-term investments.

But the title of the article does promise some debunking of myths, so let’s have a look at them. Thankfully, the myths in this particular instance came not from the speaker, but from some of the questions that were thrown up after the talk had finished and the floor had opened for discussion.

Is this lifestyle economically viable?

I was really quite surprised at this question, given how much emphasis Sonya had placed on activities like buying used goods, taking the train, and even dumpster diving, actions which typically incur much lower costs. Yet I can’t fault this misconception too much, as often sustainable living is portrayed as an elitist practice. Conversations revolve too frequently around things like electric cars, farm-to-table restaurants and solar panels, all of which can be extremely costly.

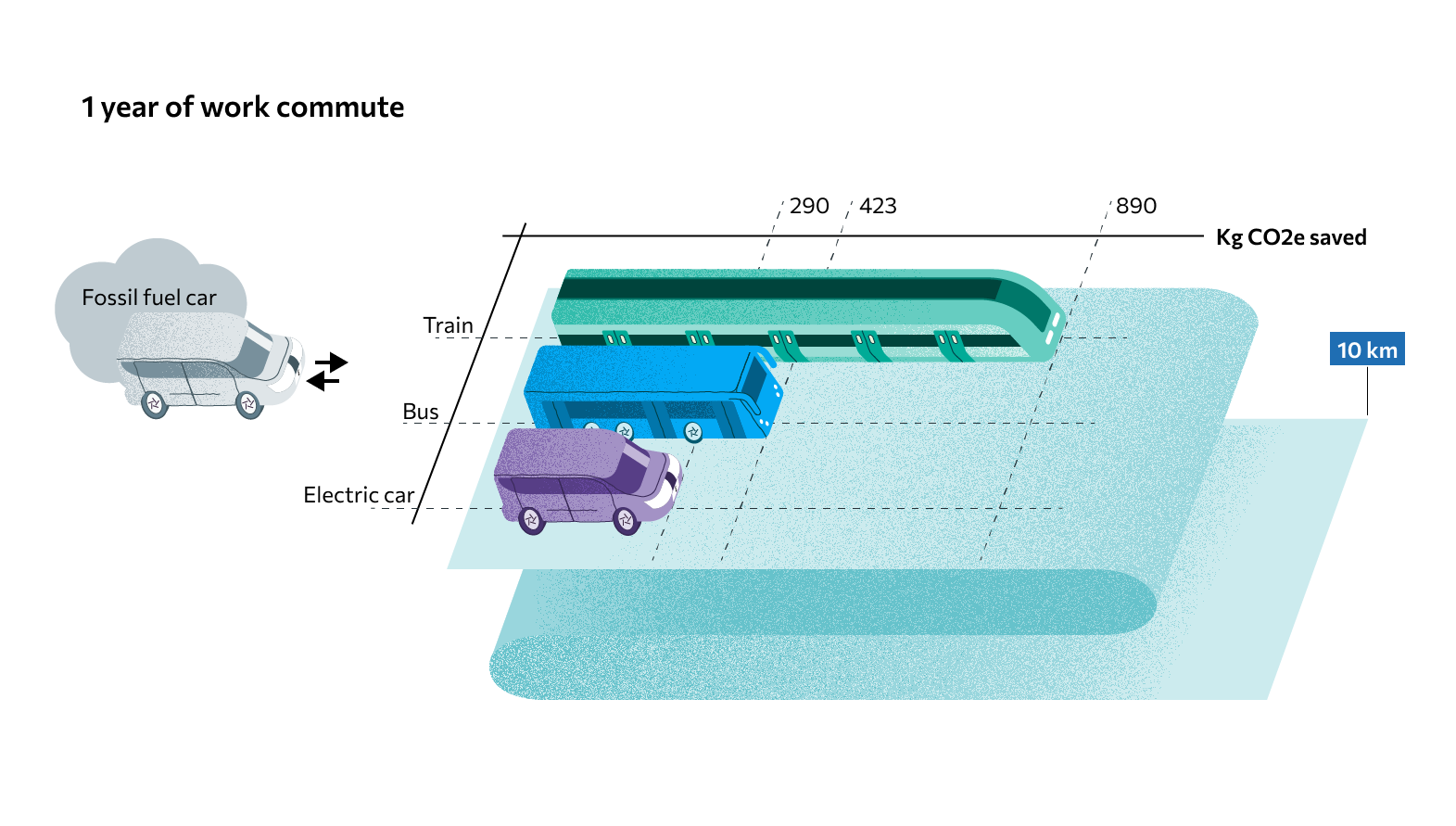

But the reality is that more effective changes are generally cheaper. Cutting out red meat usually saves costs, as does minimising wasted food. Reducing energy use by turning off unused appliances and keeping the heating down saves you a LOT of money (as much of the Global North is currently finding out). Public transport, biking or walking are always far more effective than an electric car at saving CO2e, and don’t carry with them the costs of servicing, repairs, fuel or parking.

Could you have done this without all the stuff you'd already bought?

This is absolutely a fair question. Cutting down on CO2e for a year when you already own a lot of the goods that enable your lifestyle is immeasurably easier (well not entirely immeasurable or Ducky wouldn’t exist). As an example, Sonya was an ardent skier, and already owned most of her ski equipment before she started her one tonne year. While spending more money on higher quality, longer lasting goods can actually save you money in the long run, there’s little denying that it does cost a fair bit up front. But if the area you live in has a reliable, safe avenue for buying used goods, that makes things much easier.

Buying used cuts down on CO2e emissions related to your buying of goods substantially, and has the extra advantage of generally being much cheaper. Yet in the past buying used goods has often been stigmatised, with many people avoiding it due to it being seen as beneath them, or even degrading. I’ve had plenty of experience with this, with family members both a) acting insulted at the notion their children would need our son’s hand-me-downs when offered, and b) upturned noses upon hearing that we’ve been to, or have taken our kid to second-hand stores. It’s worth noting children are probably the easiest demographic for second-hand shopping, seeing as they grow so damn fast.

Thankfully, the general trend seems to be moving away from this stigma, with second-hand shopping becoming more and more popular. It means that buying goods sustainably has become much more accessible, and no longer something that requires either excessive research or money.

We have renewable energy here, so why bother saving electricity?

This is something I hear a lot in countries like Norway, where the vast majority of local electricity is produced using hydropower. Hydropower is widely thought of as clean energy, so I can’t fault the logic here. However, looking at your electricity consumption on a strictly local scale doesn’t really reflect the reality of climate change, which is not a local phenomenon.

Let’s take Norway as an example. The vast majority of Norwegian electricity is produced using renewable means. But that does not mean that by reducing my use of electricity, I make no difference. Norway is connected to the rest of Europe through the European electricity grid, and as such when Norwegians use less electricity, that saved electricity is transferred to the rest of the continent, much of which relies on much less clean forms of electricity. Bottom line is, just because you directly consume sustainable energy, doesn’t mean you should think of it as a bottomless pit.

She didn't really make a difference you know. Look at Nord Stream

This attitude I have no forgiveness for, and I’m thankful that it was something I overheard rather than a question that was asked openly. Yes, the six to eight tonnes of CO2 equivalents that Sonya saved over the course of the year are a drop in the ocean compared to the recent Nord Stream pipeline leak.

But the changes she inspired in her friends and colleagues, not to mention in the hundreds of attendees at the talk, is what’s important. Showing how easy and practical sustainable changes to our lifestyles are is educational, and goes a long way to normalising this sort of behaviour. And when behaviour becomes normalised, corporations and governments respond, bringing about those big systemic changes we need so desperately to help save our planet.

.png?width=1002&height=842&name=Inspiring%20others%20INFOGRAPHIC%20(3).png)

In the Global North, we don’t need to eat seaweed for a year, or live like a hermit to cut down significantly on our impact on the planet. It’s a matter of making lifestyle changes which often benefit ourselves short-term, and will have overwhelmingly positive effects on our lifestyles in the long-term.

.jpg?)